Daily Life

A Norman lord is in a broad sense the head of a family, managing a household whose members he has a duty to feed, protect and clothe. He is the head of his court and manages his domain, upholds justice, entertains his guests and keeps the peace. These different duties require a central and functional facility that is strong, imposing and visible. Ultimately, this a castle, from the smallest earth and timber fortifications to the larger strongholds that have stone walls and square keeps with carefully designed internal layouts to accommodate all of these roles.

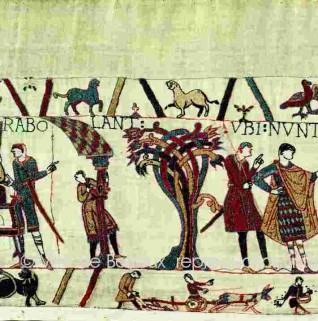

Important Norman courts formed large households around the resident family, with relatives, fellow men-at-arms, clerks, chaplains and servants. During festivities, jugglers, jesters, actors, acrobats and dancers would also be included. Indeed, since the Carolingian period, the need to organise such a crowd led to the practice of dividing up the different roles by associating them to the rooms they use: the great hall, the chamber, the chapel and the stables.

The great hall, or aula, was supervised by the seneschal (an officer in medieval noble households) and was the public space where the lord would preside when administering justice, organising a variety of ceremonies or entertaining guests at banquets. This was the space where power was demonstrated. The expression of a lord’s wealth was conveyed through wall paintings, expensive fabric, colourful furniture and wide bay windows that let in an abundance of sunlight. The officers of the court performed their duties, assisting the lord in his tasks and making sure the guests were comfortable.

The lord could then retire to his chamber, or camera, which was his private residence - managed by a chamberlain. Inside the chamber he would be joined by his family, as well as his advisers and chambermaids who made sure it was kept in order. It was a place for rest and private meetings but also entertainment, for example, board games, dice games and also jugglers and musicians who told the fashionable stories of the time. The legend of King Arthur was a great literary success that audiences enjoyed listening to at the time. Conversations were exchanged in the Anglo-Norman dialect, which was made up of ancient French and elements of the Saxon language. Speakers of this language were recognisable as members of the ruling aristocracy. The chamber was also a place for private meals. The first meal was dinner, taking place mid-morning, and then the second and last meal of the day, supper, was around four o’clock in the afternoon. Finally, the lord could take care of his personal hygiene and wash. A bathtub was brought in and many implements were available such as tooth picks, ear picks and tweezers.

The chapel, or capella, was also decorated with mural paintings and it was the household’s private church, where services would govern the order of a typical day for the court. The lord could converse with his chaplain and ask for his counsel for both religious and political matters.

Finally, the stables were managed by the constable in charge of the lord’s horses and, by delegation, the soldiers and knights who protected the household. Other servants of lower rank, such as gate-keepers, ushers, messengers, chamber maids, stable boys etc, would work in all these areas. The seigniorial household was run smoothly.

Occasionally, these different functions were divided into separate buildings, creating a large complex with a great hall. For example, the Exchequer Hall at Caen Castle had an adjoining residential palace and a private chapel within the same enclosure. The period of the Conquest led the Normans to concentrate these functions in the same building, for reasons of both security and symbolic expression. The square keeps accommodated all of these roles. The keeps of Norwich, Rochester, Colchester and Falaise, founded after the Conquest, demonstrate this reorganisation of spaces brought on by these events.

The European Union, investing in your future

Fonds Européen De Développement Régional

Fonds Européen De Développement RégionalL’Union Européenne investit dans votre avenir

INTERREG IV A France (Channel) – England, co-funded by the ERDF.

Email a friend

Email a friend  Print this page

Print this page