The ideal city is always represented in medieval illuminated manuscripts as an area enclosed by city walls and dominated by a great tower in the centre. This is the way in which the friary sees Celestial Jerusalem and the knights of letters imagine the ancient city of Troy.

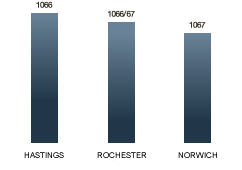

The eminence of castles in our imaginations is translated into reality throughout Normandy and England in the 11th and 12th centuries. We estimate that as many as 500 castles were constructed in England by the Normans between 1066 and 1086.

At the beginning of the Conquest the most common form of castle is the timber or stone motte and bailey castle, such as the one shown in the Bayeux Tapestry of Hastings, which was constructed as early as the first day of the conquest. Ditches and mounds surmounted by a tower can rapidly establish, with little means, an enclosed space and dominant position in the landscape. Although, in York, Norwich, Arundel, and other places, the mounds became so much more spectacular, that we guess they were perhaps intended to impress more than defend.

The other type of castle characteristic of Norman domination is an enclosed castle with a great quadrangular keep. They symbolise well-established Norman power, but the first prototypes were built soon after the Conquest in London and Colchester. Just like the vast cathedrals and abbeys, large keeps symbolise an ambition of new power through an architectural programme worthy of empires past and present. In fact, a keep is a fortress as much as a palace of beautiful stone masonry. The prince welcomes his court in the great hall on the noble floor where you can see and be seen by the surroundings it dominates. In the towns and countryside, landscapes are shaped around the pre-eminent position of the castle.

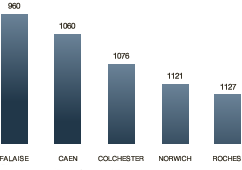

Motte and bailey castles and great towers do not exist in the English landscape before the Norman Conquest. In Normandy castles on mounds are especially identified by fortifications of modest height, which suggest troubled times. The Duke of Normandy in fact reserves the right of fortification and generally forbids the private construction of castles. In England, on the contrary, control of the land relies on the development of these private fortresses and the King does his best to maintain control from barons and their supporters. Castles therefore bring about the birth of a new aristocracy and an organisation of feudal power.

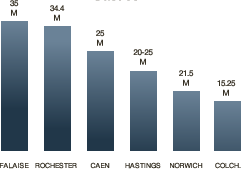

Great quadrangular keeps are reserved more for the King and great lords. They follow a model apparent in France from the beginning of the 10th century and notably in residences of the Duke of Normandy or other great lords close to the duchy. By gaining control of the duchy of Normandy after 1106, King Henry I also begins the construction of great towers such as those of Caen and Falaise.

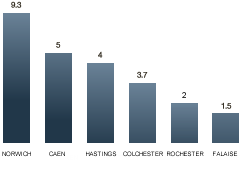

The model of great quadrangular keeps establishes itself as the symbol of Norman domination as much as the motte and bailey castle. In Norwich, these two models are combined, in Rochester the highest tower in England is constructed and in Colchester the largest in area. At the end of the 12th century Henry II Plantagenet chooses to build the great keep of Dover based on this model which had by then become archaic militarily, but which allows him to affirm his position as heir to the Norman Kings.

Email a friend

Email a friend  Print this page

Print this page